Barry Schwartz is one of the most interesting thinkers of our time.

He is most famous for his work on The Paradox of Choice.Where conventional wisdom tells us that more possibilities is better, Schwartz makes a compelling case that the abundance of choice in today’s western world is actually making us worse off. Infinite choice is paralyzing, Schwartz argues, and exhausting to the human psyche.

His TedTalk is a classic, ramping up over 12 million views.

Today, a decade later, what got crystalized into the collective unconsciousness is how subjective experiences about what is good for us can be, and often are, misleading. What, on the other hand, got neglected is that Schwartz meant his book as a social critique of our obsession with competition (even in the public domain) and maximizing the number of alternatives.

In his recent work, he has continued drawing out the societal consequences of the newest psychological knowledge, further exploring the link between psychology and economics.

It hasn’t yet received the attention of his more famous theory, but its implications are even deeper.

Let’s take a look.

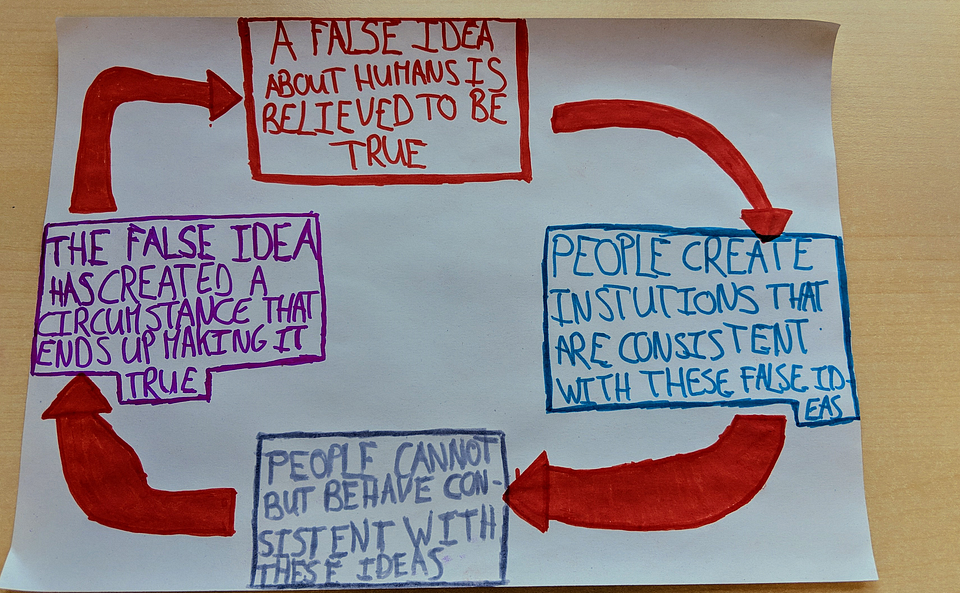

Introducing: the feedback loop of ideas about humans

Here’s the bumper slogan: human nature is much more created than it is discovered, and this has profound consequences.

To get an idea of what it means for something like human nature to be produced rather than detected, take a look at what the philosopher of science Ian Hacking calls making up people:

Take four categories: horse, planet, glove, and multiple personality. It would be preposterous to suggest that the only thing horses have in common is that we call them horses. We may draw boundaries to admit or to exclude Shetland ponies, but the similarities and differences are real enough. Arguably the heavens looked different after we grouped earth with the other planets and excluded the moon and sun, but I am sure that acute thinkers had discovered a real difference. Gloves are something else: we manufacture them. That the concept ‘glove’ fits gloves so well is no surprise; we made them that way. My claim about making up people is that [categories of people] are more like gloves than like horses. The category and the people in it emerged hand in hand. — The Social Construction of What?

Let’s unpack this a bit.

Reality does not particularly care for our attempts at dissecting it. When we decided to classify whales no longer as fish but as mammals, that did not alter their behavior.

Human beings, to the contrary, are what the Hacking calls moving targets.

They react to our classificatory practices by which we identify them, categorize them and act on these categorizations. Our labels significantlychange them, and, in turn, we are forced to revise our theoretical beliefs ‘describing’ them, which then loops back into their behavior, et cetera.

Whether Shetland ponies are considered horses or not leaves them cold.Whether humans are seen as for example, individualistic and driven by self-interest, that deeply affects how we feel, think and act.

The natural world is what it is, and will behave the way it behaves no matter what we think. But it’s not so simple with human beings. Who we are, what we are, depends on who and what we believe we are.

This is the feedback loop that is at the heart of this essay.

Ideas about humans make themselves true

Let’s talk examples.

On an individual level, we experience this on a daily basis.

For instance, in their famous study, Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobsonshowed that, if teachers, for a totally unrelated reason, falsely expect enhanced functioning from some children, their performance does increase! Meet thePygmalion effect: others’ views of someone affect the target person’s performance.

It works the other way around, too: low hopes of others decrease achievement. Scientists call this the Golem effect.

The overarching point is that expectancies could affect reality and create self-fulfilling prophecies. If you treat kids like their wonderkid geniuses, their behavior changes, their test score increases, and your false idea has made itself true. If you believe your employees are out to get you, you will run your office like 1984 and thereby sow the seeds for authority-undermining behavior and your false ideas have reified themselves.

If, even if for irrelevant or bad reasons, an economic system takes its participants to be greedy, over time, the structure that’s in place will make them behave accordingly, whether they are actually selfish or not.

“False ideas about human beings will not go away if people believe that they’re true. Because if people believe that they’re true, they create ways of living and institutions that are consistent with these very false ideas.” — Barry Schwartz, The way we think about work is broken

Our nature will be changed by the theories we use to explain and understand ourselves as human beings.

Schwartz calls this feedback loop idea technology. Science creates ways of understanding, and in the social sciences, the ways of understanding that get created are ways of understanding ourselves.

And these ways of understanding, in turn, have an enormous influence on how we think, what we aspire to, and how we act.

“Men’s views of one another will differ profoundly as a very consequence of their general conception of the world: the notions of cause and purpose, good and evil, freedom and slavery, things and persons, rights, duties, laws, justice, truth, falsehood, to take some central ideas completely at random, depend directly upon the general framework within which they form, as it were, nodal points.” — Isaiah Berlin, The Purpose of philosophy

This is the role that theories play in shaping us as human beings, and this is why idea technology may be the most profoundly important technology that science gives us.

Products of societies

So far, we’ve seen that, because humans respond to our theories about them, they change as a consequence of how we label them. False notions about what people are like make themselves true because people create ways of living and institutions that are consistent with these very false opinions. Once such a system is in place, there is really no other way for people to behave except consistent with the false assumptions on which the system is based.

The distinguished anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, said, years ago, that human beings are the “unfinished animals.” He meant that the human soul is very much the product of the society in which people live.

We design human nature by designing the institutions within which people live and work.

It hardly seems an exaggeration to say it’s a truism in Western culture that human beings are self-interested animals driven by a desire to maximize pleasure or wealth or reproductive advantage. Many people just accept that this is how humans are and that they can’t be otherwise.

Schwartz’s most flaming idea is that our economic system might be the result of a harmful view of human nature that has been making itself true. And a false one at that.

How the Keynesian view made itself true

When we decided to classify human beings as lazy and egoistic, we startedmaking them that way.

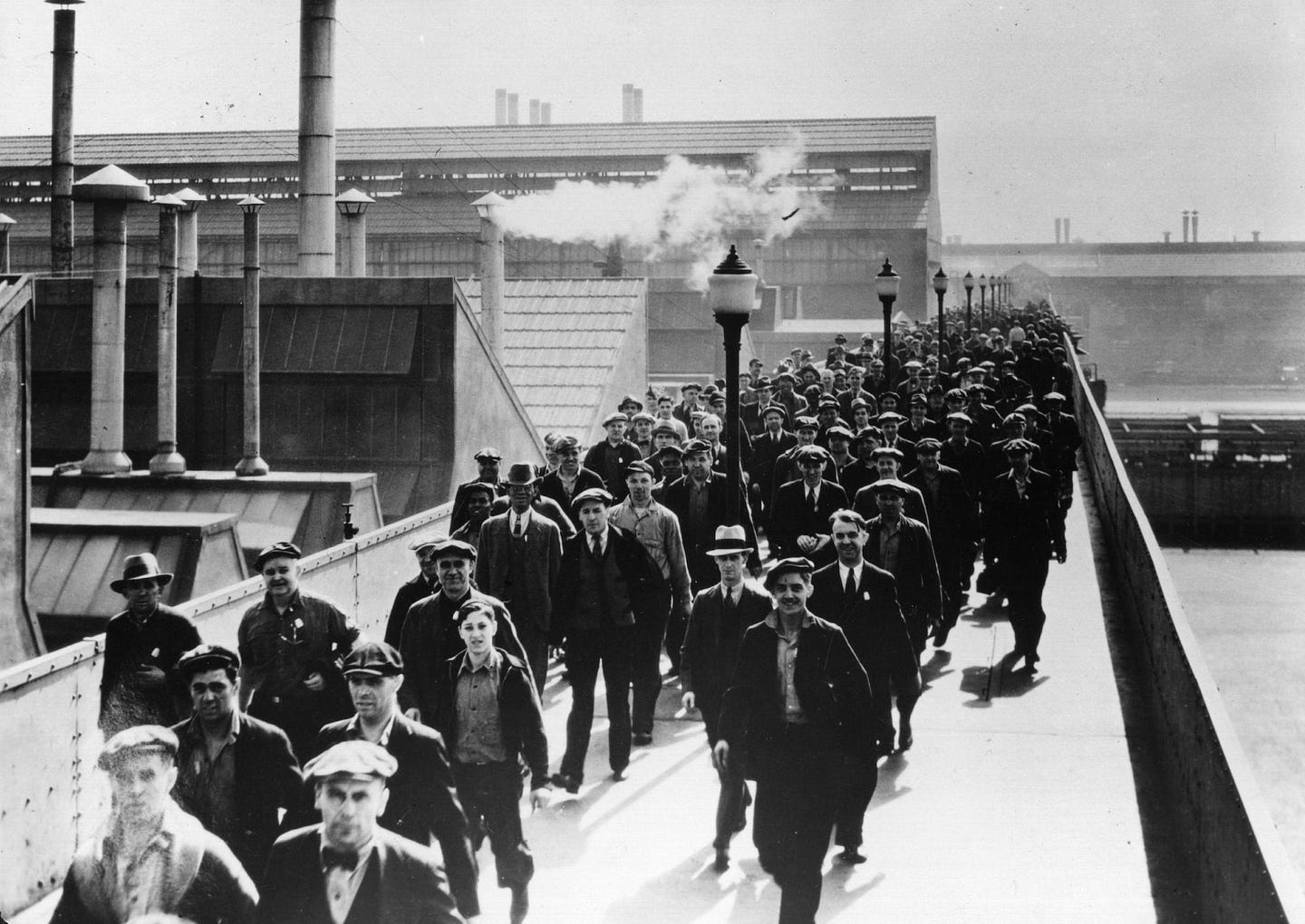

“The industrial revolution created a factory system in which there was really nothing you could possibly get out of your day’s work, except for the pay at the end of the day. Because one of the fathers of the Industrial Revolution — Adam Smith — was convinced that human beings were by their very natures lazy, and wouldn’t do anything unless you made it worth their while, and the way you made it worth their while was by giving them [material] rewards. That was the only reason anyone ever did anything. So we created a factory system consistent with that false view of human nature.”

Based on this constructed — not discovered — person who responds only to monetary incentives, capitalism established a mode of production, of goods and services, in which all the non-material satisfactions that might come from work were eliminated. Workers who do this kind of work, whether they do it in factories, in call centers, or in warehouses, do it for pay. There is certainly no other earthly reason to do what they do except for the money.

Here’s Schwartz for the last time:

“But once that system of production was in place, there was really no other way for people to operate, except in a way that was consistent with Adam Smith’s vision. So the work example is merely an example of how false ideas can create a circumstance that ends up making them true.”

And that’s how the industrial revolution created a factory system in which there was really nothing you could possibly get out of your day’s work, except for the pay.

Did anyone say “Ayn Rand”?

Why we do what we do (I): economic theory and the truth

“But hold on,’’ you raise your hand, “we don’t work in factories now anymore, do we?”

No, but the system is still in place. And a system, by definition, is “a set of things interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time.” Systems largely cause their own behavior, and, moreover, there is behavior latent in the structure of a system.

What this means is that we should (1) acknowledge that a system can be the source of its own problems rather than casting blame on individual agents and (2) try to understand the relationship between structure and behavior.

The feedback loop persists because if people believe that false views about human beings are true, they will create ways of living and institutions that are consistent with the very false suggestions.

It’s not the economy that shapes how we understand the world, it’s how we understand the world and ourselves that shapes our thinking about economy.

We taught ourselves to be power-maximizing first, to be hyper-competitive, and then created political and economic systems suited to that view of human nature.

This is the feedback loop in action.

We construct ourselves (among other things) through the language we use to talk about ourselves, and that shapes what we become and how we think.

If we talk about ourselves in the language of self-interest, then self-interested people is what we get.

What the science says

It might just well be that you’re not impressed.

“Feedback loop, be that as it may,” you growl, “but what’s wrong with a self-fulfilling prophecy that has been based on true assumptions all along?”

The bleak theory of the Homo Economicusmisunderstands why we — you and me, real people — do what we do.

In his magnum opus Human Nature and Conduct, the American philosopher

Men do not shoot because targets exist, but they set up targets in order that throwing and shooting may be more effective and significant.

Target’s don’t precede effort. The capitalistic theory of human motivation has it backwards.

There is no need to instigate action by offering incentives. You need only to do that when you want your employees to do soulless, meaningless work. For which people, of course, are not jumping with joy to spend their days on.

Psychological research confirms this common sense (right?) idea. Intrinsic motivation is much stronger than extrinsic push, and the capitalist’s insistence on the opposite is scientifically false.

Why we do what we do (II): evolutionary theory and the truth

There’s another way in which the Keynesian theory of human motivation is unnecessarily cynical.

According to allies of this doctrine such as Richard Dawkins, evolutionary theory proves that we’re all, for instance, a bundle of “selfish genes”. Our ultimate motive is always self-serving, no matter how different things may seem on the surface.

This isn’t an essay about evolutionary biology, so I’ll be brief on why this is not true.

Dawkinian selfish-gene philosophies erroneously conflate distinct explanatory levels. In particular, they commit the mistake of confusing the cause of a mental state with its content. An evolutionary explanation for a phenomenon, such as someone’s love for his/her partner, reveals nothing about the content of this person’s motivations, and doesn’t show that he/she “really” cares about his reproductive fitness and only derivatively cares about his/her partner’s welfare.

As I explain in more detail here, the conclusion that would be absolutely incorrect to draw from evolutionary theory is that human action is “really selfish”.

The feedback loop entails that it’s unwise to advertise these mistaken views because ideas about humans have a way of making themselves true:

“It would be extremely naive to regard this universal anthropomorphism as harmless. The metaphors determine our interpretation of nature in terms of classical economic competition; the interpretation of nature then feeds back to determine our interpretation of ourselves.” — Simon Blackburn, Ruling Passions

And indeed, the feedback loop has claimed its victims. Many economists claim — assume! — we will not understand human decision making until we realize that societies are collections of individuals pursuing their self-interest. And the biologist Michael Ghiselin expresses a widely shared sentiment when he memorably writes “scratch an altruist, and watch a hypocrite bleed.”

Conclusion: feedback loops, truth, and making the world a better place

And mother always told me, “Be careful of who you love

And be careful of what you do

’Cause the lie becomes the truth”

( — Michael Jackson, Billie Jean)

Genes are indifferent to our theories about them. But this is not true of individuals. Theories about human nature can produce changes in how people behave. A theory that is false can become true by people believing it’s true.

As Carl Jung said: ideas have people, not the other way around.

The result is that, instead of good data driving out bad data and theories, bad data change social practices until the data become good data, and the theories are validated.

In fact, in Power, Pleasure, and Profit, historian of ideas David Wootton argues that the self-interest picture of human nature is a recent invention, not a natural manner of looking at things. And now we erroneously believe that people are, by their very nature, motivated by genetic or monetary self-interest, that agents are “rational”, predictable utility- or power-maximizing machines whose behavior we can only modify by tinkering with rewards and punishments.

The literature on human nature is vast and I can’t here possibly do justice to all of it. That’s why the feedback loop is so important. It shows that a possible stalemate doesn’t mean that there is nothing to say about whether we should believe the Keynesian position or the scientifically supported theory.

If a debate remains undecided, we should ask ourselves a further question.When the world doesn’t give out, we should shift our focus from ‘Which theory is true?’ to ‘What would happen if we believed this theory was true?’.

What world do you want to live in?

I bet it’s not the one from Atlas Shrugged.