I felt a splitting headache — hangover, again, I concluded.

I was awakened by the beeping sound of my alarm. That, I realized, meant that it was noon and that I had to get up and that I could attend the late afternoon lecture if I would be really fast. (I had stopped caring for morning classes a long time ago.)

Still in bed, the metally, disgusting scent of old alcohol reached my nose. Flashes of last night came back. It had been a usual weekday evening at my fraternity house, meaning I didn’t really remember a lot.

Head pounding, I got up. I checked the room — no vomit, thank God. My eyes told me that the sink was dirty and my nose informed me that it was high time to change the sheets — probably the last time was months ago.

Getting dressed, I accidentally caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror. I had gained twenty kilos since I moved here, for sure.

I looked like a fat, homeless person.

By my own lights, I was a loser.

I felt an impulse to cry — what, for God’s sake, was I doing with my life? — but repressed it.

If I could just prevent confrontation with reality, everything would be fine. Besides, I didn’t have time for this kind of bullshit.

I went on with my life — pretending to be happy on the outside but breaking down on the inside.

Authenticity?

For years, I convinced myself not to care about how I looked ‘on the outside’, dismissing all such concerns as shallow.

‘I am just not like that’, I would tell myself. ‘I am not one of those fancy guys looking all nice. If I were to start caring for such superficial matters, I wouldn’t be me anymore.’

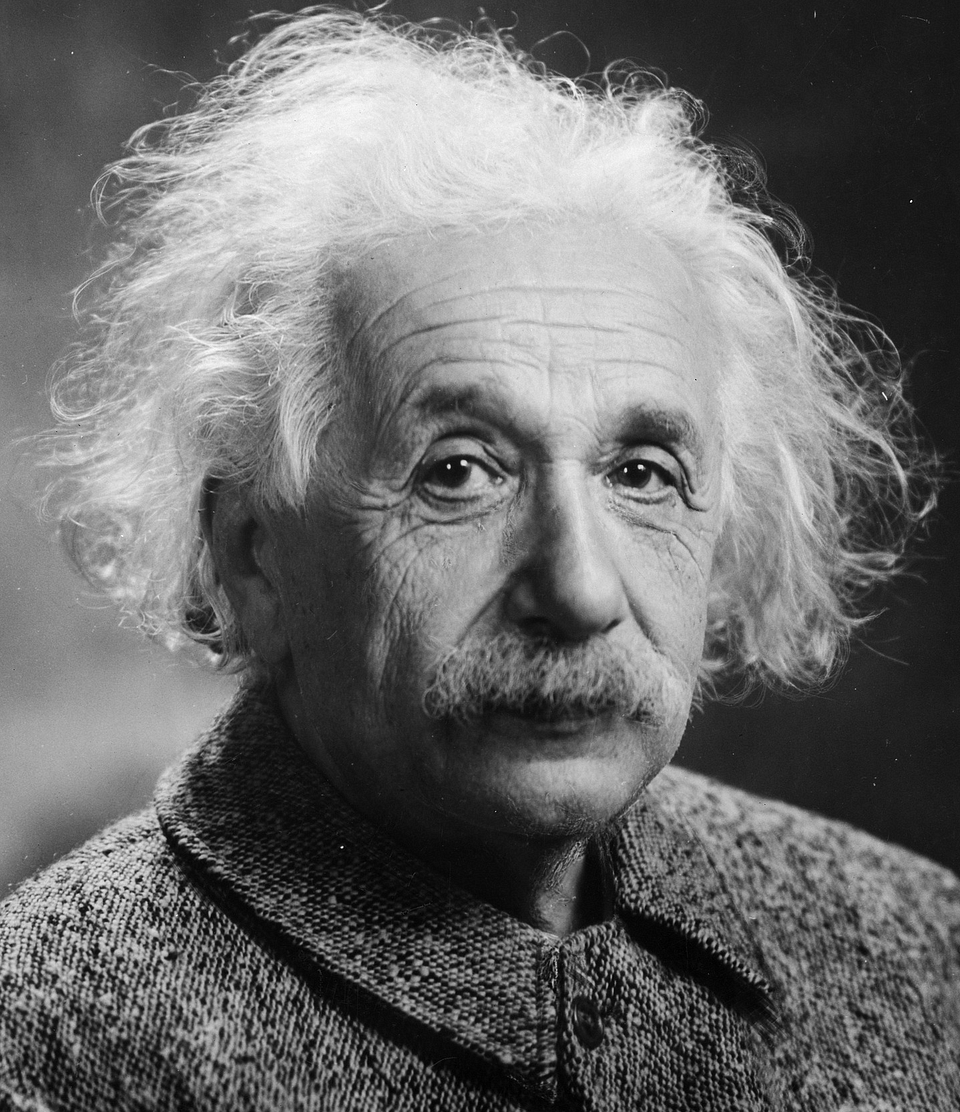

Those days, I would tell myself that, at least, I was authentic. As Einstein once said:

“If I were to start taking care of my grooming, I would no longer be my own self.”

Now, I think that I was (and Einstein was) mistaken in being so dismissive of outwardly concerns.

The Fraudulence Paradox

Before we come to that, we should acknowledge that there is something right in this way of thinking: no one likes phony people.

A compelling essay by Charles Chu brought to my attention that novelist David Wallace aptly captures this in his “fraudulence paradox”:

“The fraudulence paradox was that the more time and effort you put into trying to appear impressive or attractive to other people, the less impressive or attractive you felt inside — you were a fraud. And the more of a fraud you felt like, the harder you tried to convey an impressive or likable image of yourself so that other people wouldn’t find out what a hollow, fraudulent person you really were.”

This is an expression of the widely shared intuition that ‘what matters is the inside, not the outside’. And of course, that’s true.

But there is a difference between betraying yourself or ‘faking’ on the one hand and appropriately designing your ‘external’ appearance on the other hand. The latter doesn’t entail the former — it’s not always the case that prioritizing impression management is a sign of fraudulence.

This is an important difference that is all too quickly overlooked by geeks like me who (used to) appeal to their “own self” to defend their refusal to “take care of their grooming”.

It’s just talk

Smart talk about being true to your real self is fine and all that, but, at some point, words run out and reality catches up with you.

For me, that was when I, in an unguarded moment, saw holiday pictures of my ever-expanding body.

My confrontation-avoiding strategy had failed and it hit me like a bomb.

I still remember the moment. Seeing my repellent presence, something snapped. A sudden upheaval of rage exposed my indifference as fake. As they say, I wasn’t disappointed, just very angry.

How could I do this to myself?

I realized: there was only one person who I was hurting with my stories about being the real me and that was the real me.

On the spot, I decided to quit the fraternity, move somewhere else and start holding myself responsible for my life and my looks.

No more excuses.

The Fraudulence Paradox revisited

For me, this experience suggests that the fraudulence paradox is not entirely accurate.

Wallace postulates a linear connection between the amount of effort one puts into outside looks and one’s lack of self-esteem: the more you attempt to “appear impressive to other people”, the more you are actually “a fraud”.

I think this is incorrect. This strict correlation between impression-management efforts and fakery only applies beyond a certain basic level of impression-management that we all should engage in for our own sake.

It’s not the case that any attempt to boost your appearance betrays a lack of self-esteem. This only holds when one invests too much effort in these matters.

Moreover, disavowal of these basic forms of impression management is similarly a result of inferiority feelings and not of some enlightened insight into the shallowness of external appearances.

Self-Respect

It’s not only too much grooming that is the consequence of inner hollowness. The same can be said of not paying enough attention to one’s looks; failure to do so results from low self-esteem as well.

The truth is that you deserve to look good — you owe it to yourself to present yourself in a minimally decent way (or to try to appear attractive to other people to at least some extent). Hiding behind intellectual stories about how you are not the type of person who cares much for demeanor doesn’t change that. Ultimately, such behavior does not result from some discovery about the futility of cultural norms but from a conviction that you’re not worthy of looking awesome.

Deep down, treating your external presence as negligible flows from a failure to see that side of you as something you don’t need to be ashamed of.

Personally, this was one of the most difficult and important realizations I’ve had during my life.

Intelligence = happiness?

Intelligent people using their brains to diagnose attention to one’s guise as covering up ‘the real deal’ (our ‘insides’) often hold a belief that comes down to something like “I want people to take me as I truly am, not as I appear on the outside”.

This was my prime excuse for ignoring my appearance.

Consequentially, I’d say things like “I don’t want to bother dressing up for a date, because she better like me for who I am, not for how I look”.

Let me tell you how that went for me: not well.

If you think that your life will be better because you are at least “true to your own self”, you’re wrong. Authentic or not, people living according to such philosophies often turn out bitter, cynical, unlikable and unhappy.

Way to go, intelligent person.

Two defense mechanisms

I had to face the truth: for better or worse, how I look is important and citing smart-sounding theories about paradoxes wasn’t going to change that.

What’s more, these theories were defense mechanisms — rather than good arguments — for my behavior.

For starters, it’s simply not true that any effort to appear impressive to others is a sign of fraudulence.

In reality, not doing so results from an inner lack. Not engaging in impression management provided me with an all too convenient excuse for not having to treat the way I look as an aspect of myself that deserves attention.

I had to start seeing myself as worthy of looking good.

Secondly, refusing to engage in impression management does not prove that one is legit.

This excuse would go something like this: Thanks to my True Sight ability, I can see through the pretensions of others. I know what people are “really” like underneath the niceties. I, by contrast, am not a pretender. I am real and want people to like me for who I am ‘on the inside’.

This is bullshit. I am smarter than this.

Balancing values

Perhaps Einstein was right and “taking care of his grooming” would amount to embracing a value his “own self” doesn’t hold dear (though I doubt it), even then it might be wise to attach more weight to other considerations than to concerns about authenticity.

Manifesting a characteristic that one interprets as representative of one’s true self is a value, to be sure. But there are other important values — having a good life — that matter greatly, too.

Like to read?

Join my Thinking Together newsletter for a free weekly dose of similarly high-quality mind-expanding ideas.