Everywhere I go, I’m within earshot of someone ranting about capitalism. How it’s to blame for all the issues in the world — and in the angry person’s life. Inevitably, others will join in and before I realize it I’m in the middle of a Capitalism-Fucked-The-World-Up support group.

If you give the same reason for every issue — global warming? capitalism; the financial crisis? capitalism; my divorce? capitalism — that warrants suspicion about your thoughtfulness. So frankly, this anti-capitalism attitude has always struck me as lazy thinking.

Blaming ‘capitalism’ is hardly specific enough to identify the deficiency, let alone to work out a well-supported solution.

But you know me, I’m curious, and it’s interesting to listen to what people say, so during my holidays I embarked on a mission to understand these complaints.

I couldn’t believe what I found.

Capitalism creates bullshit jobs?

When people blame capitalism, “capitalism”, I think, refers to a particular way of organizing society. Since Karl Marx and probably before that, the capitalist way of structuring the economy has been charged with allowing capital to take advantage of laborers — sowing the seeds for exploitation.

Bullshit jobs are the Western, 21st-century version of this pointless toil.

Bullshit jobs, as defined by David Graeber (the anthropologist who coined the term), are jobs that are redundant according to those who have them.According to his oft-cited survey results over a third of all employees think that their form of paid employment does not contribute anything. Graeber concludes:

“Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed.”

Some go further, and also accuse the ‘the system’ of tricking the rest of us, those who don’t ‘admit’ to having a bullshit job, into falsely believing that our efforts have significance:

“One of the greatest triumphs of capitalism: convincing workers that labor is ‘meaningful’”. — Andrew kortina

The exploitation is total.

If many people in different jobs judge their daily grind to be meaningless, that would lend support to such generalizations. However, recent studies have cast doubt on Graeber’s data. While Graber’s estimations turn out to be based on sketchy data gathered by a commercial party, official surveys paint a picture according to which “socially useless jobs” (the academic term for bullshit jobs) are less common than previously believed. From a recent study:

We use a representative dataset comprising 100,000 workers from 47 countries at four points in time. We find that approximately 8% of workers perceive their job as socially useless, while another 17% are doubtful about the usefulness of their job.

While Graber’s speculations are based on half-baked ‘evidence’, more thorough empirical investigations indicate that he has overstated his case. By extension, claims that capitalism has “tricked” us seems to lack support. If about 90% of “workers” judge their work to be useful, it requires stronger evidence to show they’re all deluded. Until capitalism-jeekers present evidence of such mass-hypnosis, they need to stop making up stories about people who work a lot being tricked by capitalism or having psychological issues — it’s (mostly) untrue and quite offensive.

Moreover, even if Graber’s extrapolations weren’t exaggerations, capitalism isn’t responsible for people accepting bullshit jobs. Rather, capitalism seems toenable us to fulfill our childish desire for social status — a desire our species felt long before capitalism. Consumerism provides a way of gratifying ourneed to keep up with the Joneses: the acquisition of material goods as measure of success offers a quick route to excelling your neighbor. This need is deeply human — as we’ll see below — not exclusive to homo sapiens in capitalist societies.

Capitalism didn’t change human nature

Another charge often leveled against capitalism is that it brought about a fundamental change in the human soul.

For example, in How Much Is Enough? Money and the Good Life we read that

“Experience has taught us that material wants know no natural bounds, that they will expand without end unless we consciously restrain them. Capitalism …has taken away the chief benefit of wealth: the consciousness of having enough.”

The claim is that, thanks to capitalism, our wants have gone out of control and we now desire excessively.

Capitalism is an easy target, but, again, this accusation doesn’t survive reflection. Charles Chu gives the correct reply to this:

“It is unfair, I think, to blame capitalism for destroying “the consciousness of having enough.” Evolutionary theory has taught us that all living creatures have a natural drive to survive and reproduce. The endless pursuit of more is part of human nature, not the result of a capitalist society.”

People crave bragging rights. Before shinier cars, there were fancier wigwams. At most, capitalism can be charged with bringing out these tendencies in us. Again, though, blaming capitalism for causing this behavior lets ourselves off the hook way too easily.

The excessive consumption and environmental crises that comes with satisfying the rich Westerner’s need for social status are terrible, but capitalism isn’t exactly holding a gun to our heads when we purchase that new car. That’s all on us.

There’s more going on.

‘‘Capitalism’’ doesn’t have exculpatory power — or does it?

Perhaps it is this: people often blame capitalism for encouraging certain behavior. For instance, capitalism is said to impose a perverse incentive structure, rewarding people for un-rewardable — morally wrong — behavior.

While this observation is probably correct, it doesn’t go as far as the capitalism-jeeker wants is to go. Imagine a greedy hedgefund manager, his soul thoroughly bent out of shape due to capitalist influences, who, when people ask him why he was such a selfish dick, claims that “capitalism made me do it.” We wouldn’t buy the excuse. He’s still to blame.

When people behave obnoxiously, shouldn’t we hold them accountable, rather than the way their society happens to be structured?

Perhaps, again, capitalism brought out these perverse tendencies in those people, but, as our response to the hedgefund manager’s plea of innocence indicates, it seems wrong to say that capitalism — and not the person —bears responsibility.

Or so I thought.

This was my first reaction, but I later realized this rebuttal is too quick. If you’ve been following the news for the past decade, you probably can’t shake the impression that there seem to be structural forces producing the same repeated errors. That suggests that the cause of these moral faults is systemic:

“Conspiracies in capitalism are only possible because of deeper level structures that allow them to function. Does anyone really think, for instance, that things would improve if we replaced the whole managerial and banking class with a whole new set of (‘better’) people? [Yes, I did.] Surely, on the contrary, it is evident that the vices are engendered by the structure, and that while the structure remains, the vices will reproduce themselves.” — Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism

This, I now believe puts the finger on the sore spot. In the rest of this essay, I will try to show that capitalism has produced a perverted elite, and numbs the moral consciousness of the rest.

Capitalism and today’s moral impoverishment

Tragically, in a capitalist society greed can run amuck. Managements are sometimes tolerated or even embraced who should not be — managements preoccupied with self-interest, managements blind to their own ethical lapses, managements with a record of racist or misogynist or homophobic tendencies. Boards of directors afflicted by conflict or indifference will sometimes look the other way at the actions of their management teams.

Everyone knows the famous movie line, when Gordon Gekko told us that “greed is good.” Coded to maximize shareholder value, our economy, as Tim O’Reilly has said, runs on the wrong algorithm.

For example, this devastating New York Times longread exposes how, in many countries, McKinsey’s consultancy work knowingly strengthens abhorrent regimes. McKinsey, in turn, defends its clientele by claiming that change of corrupt governments is best achieved from the inside, but the NY Times report reveals that expression of good intent to be dubious at best.

To begin, it’s not at all clear that they have these intentions. The article cites Calvert Jones, a researcher from Maryland University who has been studying these practices for almost 20 years:

“Outside experts might even reduce, rather than encourage, domestic reform, Ms. Jones said, partly because consultants are often unwilling to level with the ruling elite … “They self-censor, exaggerate successes and downplay their own misgivings due to the incentive structures they face.””

I wonder why they’d do that if they’re so keen on improving the world?

And if they do mean well, their strategy for achieving ethical change misfires, and in some cases makes things worse:

Robert G. Berschinski, a State Department official in the Obama administration, said business leaders and policymakers often believed that actively engaging with authoritarian governments would lead to economic reform, which in turn would drive political reform. “But what is becoming increasingly clear, in Russia, China and Saudi Arabia — in all three of those instances — that belief has not proven to be true,” he said.

Some of these people are straightforward about this. My flatmate, who works at Morgan Stanley, almost laughed at me when she had to convince me that it’s their own wallet (i.e. the market demand), and not concern for the environment, that persuades banks to offer ‘green accounts’. And thishilarious account by a Goldman Sachs trader of his experience at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business offers an interesting peek into the workings of their minds:

“ One class was about … how corporate mottos and logos could inspire employees. Many of the students had worked for nonprofits or health care or tech companies, all of which had mottos about changing the world, saving lives, saving the planet, etc. The professor seemed to like these mottos. I told him that at Goldman our motto was “be long-term greedy.” The professor couldn’t understand this motto or why it was inspiring. I explained to him that everyone else in the market was short-term greedy and, as a result, we took all their money. Since traders like money, this was inspiring. … He didn’t like that motto … and decided to call on another student, who had worked at Pfizer. Their motto was “all people deserve to live healthy lives.” The professor thought this was much better. I didn’t understand how it would motivate employees, but this was exactly why I had come to Stanford: to learn the key lessons of interpersonal communication and leadership.”

Not everyone is so honest. Others — most — seem to have double standards. The NY Times critique astonishingly reveals how McKinsey’s work in Saudi Arabia helped the regime to better execute their anti human-rights measures. Of course, McKinsey was quick to sympathize: it was “horrified by the possibility, however remote,” that their report could have been misused.

Such cases everywhere once you look for them. For instance, during a recent interview, the ex-politician and former European Commissioner Neelie Kroes said that she, at that time, actually should have been sitting in the plane to attend a meeting on NEOM, the futuristic resort that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is building. Until recently, international investors were eager to step into the project. But after the after last month’s killing and dismemberment of a Washington Post columnist by Saudi agents, things became a lot more difficult.

Kroes was a member of the project’s advisory board. When asked why she had linked her name to a brutal dictatorship, she replied: “When I talk to the crown prince, I have the chance to talk to him about my views on, for example, the freedom of expression.” That opportunity, apparently, justifies teaming up. (You should be skeptical about such rationales by now.)

Meanwhile, the crown prince isn’t exactly changing his mind after these intimate conversations. Bin Salman’s regime has, for example, imprisoned many peaceful activists. Eighteen of them are women. In prison, Amnesty International reported, they are tortured and sexually assaulted.

According to The Wall Street Journal, these tortures are instigated by a close confidant of the crown prince himself. The apparent reformist tendency of Bin Salman — Saudi women get to have a driving license and a place in the cinema — is nothing more than quasi-progressive window dressing, meant to give the West the comfortable illusion that things are moving in the right direction.

See how this works?

Okay, we’ll do one more example. According to Sheryl Sandberg, member of Facebook’s board of directors, “at its best Facebook plays a positive role in democracy.” Recently, it was revealed that she is closely involved in the recent privacy scandals surrounding Facebook, and also personally instructed staff to find out whether philanthropist and CEU-founder George Soros, who criticized Facebook, could be taken down. Since then, feminist organization Lean In’s, number-one priority has been to distance herself from her.

Zooming out, a pattern emerges in which the elite deceitfully combines the rhetoric of social responsibility with the rapacious pursuit of profit.Involvement in a progressive cause is all too often used as a smokescreen for unscrupulous cynicism. The feminism of Kroes and Sandberg and the nice words of McKinsey are nothing but ‘image laundering’.

In Winners Take All; The Elite Charade of Changing the World, former McKinsey consultant Anand Giridharadas exposes the ‘improve-the-world-as-long-as-you-benefit’ mentality of today’s economic elite. Giridharadas doesn’t dispute that good work is being done. His point is that many powerful people aren’t willing to accomplish fundamental changes as soon as their self-interest is no longer served by it. What perhaps once were progressive ideals is now merely a moral conscious that needs to be suppressed, if not silenced.

Because, make no mistake, their self-interest always comes first.

Capitalism: good for who exactly?

Especially in the US, the conviction that Millennials are the first generation to be worse off than their parents is gaining ground:

“[Compared to previous generations,] what is different about the world around us is profound. Salaries have stagnated and entire sectors have cratered. At the same time, the cost of every prerequisite of a secure existence — education, housing and health care — has inflated into the stratosphere.”

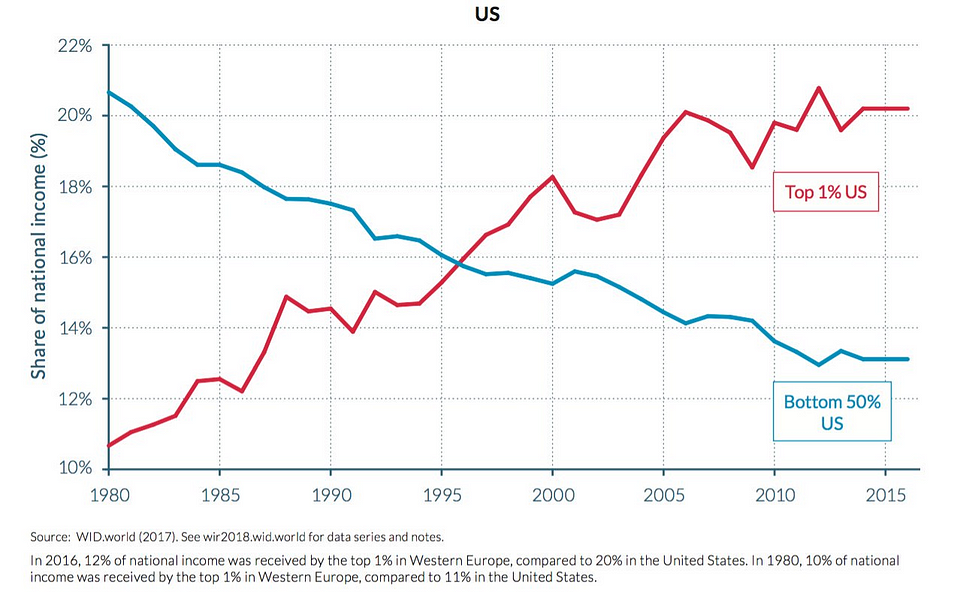

Co-occurring with the rise of capitalism, the modern world has seen a startling rise in financial inequality. Since the implementation of neoliberal policies in the late 1970s

“The share of national income of the top 1 percent of income earners soared, to reach 15% … by the end of the century. The top 0.1 percent of income earners in the US increased their share of the national income from 2% in 1978 to over 6% by 1999, while the ratio of the median compensation of workers to salaries of CEOs increased from just over 30 to 1 in 1970 to nearly 500 to 1 by 2000. … The US is not alone in this: the top 1 percent of income earners in Britain have doubled their share of the national income from 6.5% to 13% since 1982.” — David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism

Reading that, I can’t shake the eery feeling that neoliberalism intends to (1) re-establish the conditions for capital accumulation and (2) to restore some kind of kleptocratic power for economic elites. It sounds like a conspiracy theory, but is it?

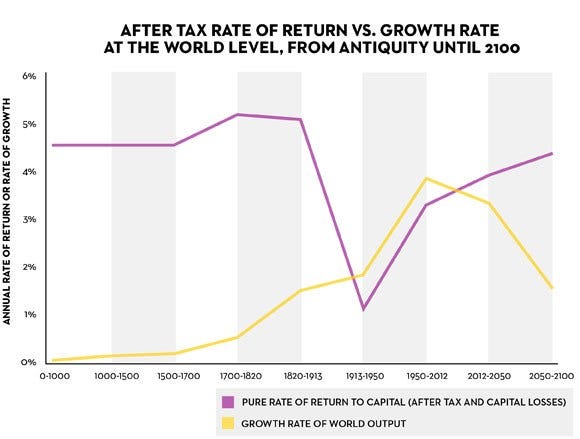

According to the French superstar economist Thomas Piketty — some scientists put him up there with the likes of Adam Smith, Karl Marx and John Keynes — it might well not be. In his magnum opus Capital in the Twenty-First Century, he disproves the neoliberalist promise that the free market will distribute wealth equally. While it has traditionally been thought that market forces decrease economic inequality — economists call this the Kuznets curve — Piketty’s data shows that wealth, in fact, does not ‘trickle down’ at all. Rather, in a properly functioning free market, inequality is set to increase:

Let’s analyze. The purple line shows Piketty’s estimate of the rate of return on capital going back to antiquity and forward to 2100. The yellow line shows his estimate of the economic growth rate over the same period. The purple line indicates that the wealth of the possessing class (land, houses, machines, shares, savings, etc.) grew faster than the economy for almost two thousand years — indicating that people with property had higher returns than people who worked. The return on capital was between 4 and 5 percent, while the annual growth of the economy was well below 2% (see the yellow line).

The twentieth century, containing two World Wars, far from representing normality, was a historical exception unlikely to be repeated, Piketty argues. In the normal eras, the growth rate has been below the rate of return, implying steadily rising inequality. If capital yields a higher rate of return than the economic growth rate is, those with capital will own an increasingly larger piece of the pie.

Rather than fostering equality, the free market, in its default mode, widens the gap between those who have and those who have not.

Let’s look at a concrete example. In August 2017, the Financial Post featured a story titled “Something has gone awry with the Philips Curve.” The Philips Curve predicts that less unemployment leads to higher prices. This chain is somehow broken. In the USA, for instance, since 2010, as the unemployment rate has fallen from 10% to 4.4%, inflation has hovered between 1% and 2%. Where did the chain break? Prices aren’t increasing as a result of rising employment because salaries aren’t increasing. Wage growth held at around 3.5% year-over-year, but has been stuck around 1% since 2009. If corporations don’t respond to increased profits by raising pay, that means that an increasingly larger slice of the pie goes to the owners of capital while the suppliers of labor get a smaller piece of the total amount of value that we produce. It’s exactly the kind of pattern that Piketty would predict, and yields a picture like this:

As the chart shows, in the US, while the income share of the richest 10% has continuously risen since the 1980s, the share owned by the bottom 50% of the population dropped.

“Perhaps globalization has gone too far,” you reply, “but is also the driving force behind the most important development in the last 40 years: the phenomenal growth in prosperity in 2.5 billion (!) people in China and India. Many countries — Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Signapore — that achieved a ‘Western’ standard of living did so by opening up to the world market. Surely, 2.5 billion people count for something?”

They do, and the emphasis on economic prosperity disguises the rest of their story. While China, for example, lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, Chinese people have not at all been granted more civil or political rights. Economic growth doesn’t seem to father moral progress.

And while, acknowledged, their material conditions have improved, income disparity is an even bigger problem in emerging countries. The gap between rich and poor has increased in nearly every region in the world over the past few decades.

Capitalism numbs: how ethics became irrelevant

Wow. In a capitalist economy, increasing inequality is the rule, not the exception. And despite their ostentatious ideals, it is precisely such elites who instill distrust in society through their fakeness. The widespread scale of these vices suggests that, while they are instantiated in individuals, their ultimate cause might be systemic.

If you’re cynically disposed, you might reply: “So capitalists want to make money and some powerful people are hypocrites, got any other news?”

To begin, this response underestimates the seriousness of the situation. But since you ask, yes, I do have other news. It’s not just the elite who are morally impoverished.

In their legendary 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels observe:

“[Capital] has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of Philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation.It has resolved personal worth into exchange value.”

Almost 200 years later, this is as true as ever. These days, everything is evaluated in terms of money alone. In politics, there is an ever stronger tendency to reduce every social issue to a calculation, a financial-economic issue. Parties across the political spectrum share this implicit ideology and always seek the same solutions: more market, less government, more growth.Politics is no longer a battle of ideas, but pretends that all choices are financial ones.

This, for example, loops back to the point about bullshit jobs: while I don’t think the human need for social status is a product of capitalism, the mindset that more jobs — even if they’re pointless — is always a good thing because it contributes to economic growth might well be.

Today, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism, philosopher Slavoj Žižek quips in Living in the End Times. His remark gets at two things. It registers the widespread sense that capitalism is the only viable political and economic system and it diagnoses that all of us have great trouble imagining a coherent alternative to it. The historian Francis Fukuyama is famous for writing that we may be witnessing The End of History and the Last Man. We’ve arrived at “the end of history”, because liberal democracy is the final form of government — there can be no progression (only regression) from liberal democracy to an alternative system. Whatever its merits, Fukuyama’s thesis that history has climaxed with liberal capitalism is accepted, even assumed, at the level of the cultural unconscious.

The feeling that neoliberalism is the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution, has caused political and cultural sterility. ‘Economic growth’ or ‘more money’ should not be the main considerations in the societal debate, but politicians have become technocrats who pursue only these causes.

Pulling it all together, the biggest problem with capitalism is, I believe, that it seems to distort, no, cancel, moral compasses. We know the price of almost anything but the value of almost nothing. For many, the only way of hearing the words ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is as ‘more money’ and ‘less money’. We try to eliminate ethics by trying to look for an objectivity that isn’t there.

I think the recent crises show that the problems of our time ask for an answer that goes beyond numbers, an answer that is rooted in a clear vision of a good life. Morality should play an important role in political debate, but fake morality is the new “opium of the people”. Anyone who, when the cameras are rolling, shows that his heart is in the right place, that his company is committed to a better world, can continue to act abhorrently when behind the scenes.

Somehow ‘we’ have developed a weird

Like to read?

Join my Thinking Together newsletter for a free weekly dose of similarly high-quality mind-expanding ideas.