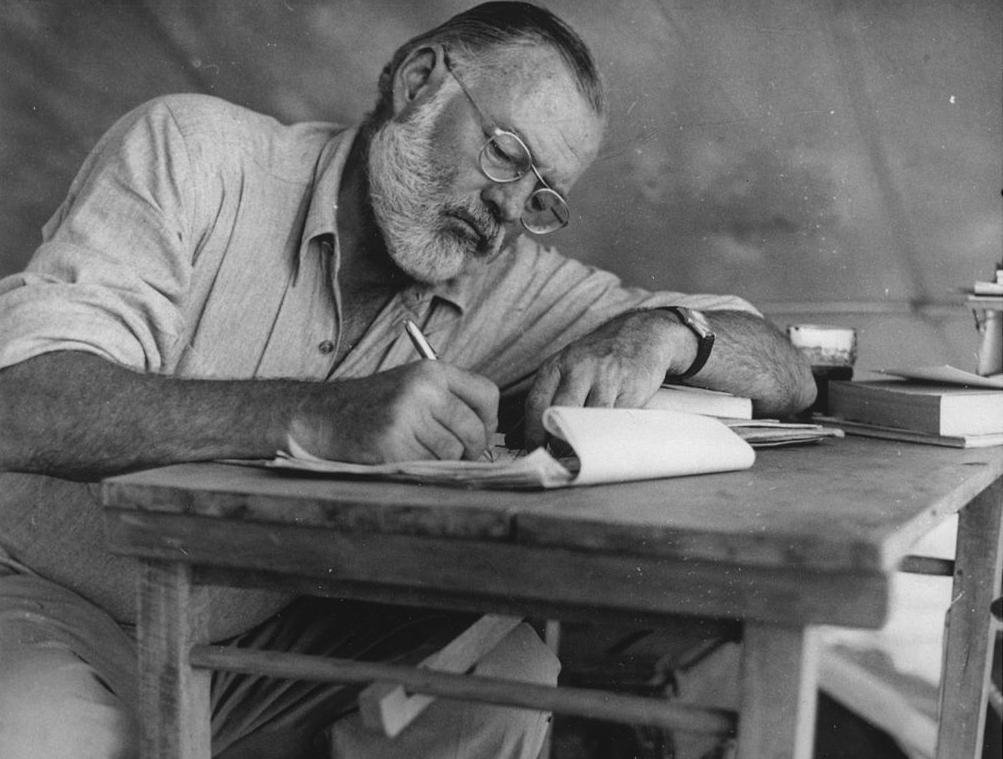

Chances are, if you do some writing, you’ve come across the quote of Ernest Hemmingway about his writing routine where he says he

“Learned never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it. I always worked until I had something done, and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day.” — Ernest Hemmingway

There’s a little bit more to it though.

It’s one thing to know what will happen next before you call it a day. It’s quite another to literally stop in the middle of a sentence, as Hemmingway did.

Is that a practice we should emulate?

The power of momentum

Hemmingway’s rule was to end a writing session by taking some baby steps into tomorrow’s territory. Instead of closing up shop when today’s section — or whatever — was finished, Hemmingway started on the next paragraph as well. And then, after a few lines, he’d abruptly stop, in the middle of a sentence.

It’s not that he was stuck. He knew how to go on, but he refused to commit the words he had in mind to the paper.

Why? Because, this way, he guaranteed himself an easy start the next day. After all, he had already figured out how to continue the story. The words were already — or: still — there, stored in his unconscious mind.

Hemmingway realized that the hard part of writing is starting, creating something out of nothing, so he made sure he wouldn’t have to face that predicament. Instead of confronting an empty document, Hemmingway could just start writing by finishing the sentence he had deliberately left unfinished the day before and see where momentum would lead him.

Before you realize it, these daily 500 words are on the page.

Getting it going

When I started writing, I made the mistake Hemmingway’s technique is designed to avoid all the time.

I would sit down at my desk, a vague topic in mind, and say to myself: “Let it happen, oh Lord!”

Of course, the sesame gates of my mind refused to open.

Frustrated, I concluded that I ‘wasn’t ready’.

In attempting to solve this problem by applying Hemmingway’s advice, however, I ran up against one small problem: I don’t write every day, but usually have one or two Writing Days per week. When one continues one’s writing not the next day but only several days later, I found, stopping mid-sentence loses some of its utility. Due to the extended time gap, the idea behind the half-sentence would elude me, and it still felt like starting from scratch. The words, or train of thought, that my past self had purposefully left unwritten were buried too deep by now.

And so, although I could start from the middle of a sentence, momentum never showed up.

When your writing days are further apart, then, there must be a better way to get the juices flowing when Writing Day comes.

Keep your subconscious on it

To do this, I use a technique inspired by Thomas Edison, who advised to

“Never go to sleep without a request to your subconscious.”

The idea is to intentionally direct the workings of your subconscious mind while you’re sleeping. I don’t know if this exercise trades on a placebo effect or sets something more real in motion, but anyway, it works.

Every night, I take out an empty piece of paper and jot down some thoughts and a follow-up question relating to the article scheduled for this week’s Writing Day (usually Saturday).

For example, when I was crafting the piece on Two Ways To Think, the question for Monday was: ‘Why is truth not the right criterion for evaluating most beliefs?’ On Tuesday morning, I answered; ‘What is the function of cognition?’. Etcetera.

Every morning, literally the first thing I do after waking is stumbling to my desk and to harvest the fruits of my unconscious by answering last night’s question.

This of course adds up, but, more specifically, it accomplishes two things.

It keeps your unconscious with this week’s piece continuously. That’s why, if you don’t write daily, this schedule might be more effective for you in harnessing momentum than Hemmingway’s trick. I often get small but compounding flashes of insight during the week, which I save in Evernote. I believe that these sparks of inspiration are a direct consequence of the daily journaling, and that my unconscious wouldn’t toss me so many useful thoughts without it.

Secondly, this ensures that you’re not starting from scratch when Writing Day comes. Rather, you have your handwritten notes and Evernote entries as starting materials. That’s a lot less pressure than staring at a blank page.

This habit of spending 10 minutes in the morning and 10 minutes at night thinking about the article, recording my stream of consciousness, has been a game-changer for me.

Take advantage of incompleteness

And I suspect that this unconscious processing is also what makes Hemmingway’s method so effective. Hemmingway’s incomplete sentence does implicitly what the nightly question does explicitly. Ending the workday with an incomplete sentence launches the same mechanism as the daily journaling — giving your unconscious an assignment.

Indeed, psychologists have discovered that that interruption can in fact improve, rather than hinder, a person’s ability to remember. This is called the ‘Zeigarnik effect’:

“Lithuanian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik observed the effect of interruption on memory processing in 1927. Whilst studying at the University of Berlin, her professor, Kurt Lewin, had noted how waiters in a cafe seemed to remember incomplete tabs more efficiently than those that had been paid for and were complete.” — PsychologistWorld

If you write daily, you can exploit this curiosity of the human mind in the same way Hemmingway did. If not, you need another way to subscribe to momentum. Trust me, daily

Like to read?

Join my Thinking Together newsletter for a free weekly dose of similarly high-quality mind-expanding ideas.